A study looking at the longer-term impact of COVID-19 has found that nearly a third of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 displayed abnormalities in multiple organs five months after being discharged. Some of these abnormalities have been shown through previous work to be evidence of tissue damage.

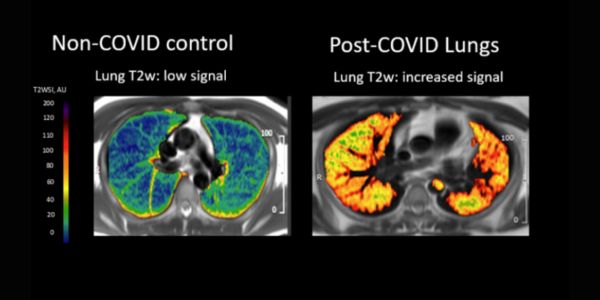

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of patients on the trial showed a higher burden of abnormal findings involving the lungs, brain and kidneys compared to controls. Lung abnormalities were significantly higher (almost 14-fold higher) among patients discharged from hospital for COVID-19 than in the control group, while abnormal findings involving the brain and kidneys were three and two times higher respectively.

The extent of abnormalities on MRI was often influenced by the severity of the COVID-19 infection the patients had experienced and their age, as well as co-morbidities.

The findings, published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, are part of the C-MORE (Capturing the MultiORgan Effects of COVID-19) study. C-MORE, a multi-centre MRI follow-up study of 500 post-hospitalised COVID-19 patients, is a key element of the national PHOSP-COVID platform, led by the University of Leicester, which is investigating the long-term effects of COVID-19 on hospitalised patients. This paper presents the results of an interim analysis of 259 post-hospitalised COVID-19 patients and 52 controls.

The C-MORE study is being led by researchers from the University of Oxford’s Radcliffe Department of Medicine and is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the NIHR Oxford Health BRC, as well as the BHF Oxford Centre for Research Excellence and Wellcome Trust.

The participants, who were recruited across 13 sites in the UK, underwent MRI scans covering the heart, brain, lungs, liver and kidneys an average of five months after discharge from hospital. They also had blood tests and completed questionnaires.

Dr Betty Raman, who is leading the C-MORE study, said: “We found that nearly one in three patients had an excess burden of multiorgan abnormalities on MRI, relative to controls. At five months after hospital discharge for COVID-19, patients showed a high burden of abnormalities involving the lungs, brain and kidneys compared to our non-COVID-19 controls. The age of the individual, severity of acute COVID-19 infection, as well as co-morbidities, were significant factors in determining who had organ injury at follow-up.”

The study found that while some organ-specific symptoms correlated with the imaging evidence of organ injury – for example, chest tightness and cough with lung MRI abnormalities – not all symptoms could be directly linked to MRI-detected anomalies.

The levels of damage to the heart and liver in the former hospitalised COVID-19 patients were similar to those in the control group.

MRI-scanners-in-the-Radcliffe-Department-of-Medicine.

The paper also confirmed that multi-organ MRI abnormalities were more common among post-hospitalised patients who reported severely impaired physical and mental health after COVID-19, as previously described by the PHOSP-COVID study investigators.

“What we are seeing is that people with multiorgan pathology on MRI – that is, they had more than two organs affected – were four times more likely to report severe and very severe mental and physical impairment. Our findings also highlight the need for longer-term multidisciplinary follow-up services focused on pulmonary and extrapulmonary health (kidneys, brain and mental health), particularly for those hospitalised for COVID-19,” Dr Raman said.

She added: “These findings are the result of extensive collaborative efforts by investigators across the UK. We are incredibly grateful to patients and the public who have participated in this study.”

Professor Chris Brightling of the NIHR Leicester BRC, who is leading the PHOSP-COVID study said: “This detailed study of whole-body imaging confirms that changes in multiple organs is seen months after being hospitalised for COVID-19. The PHOSP-COVID study is working on understanding why this happens and how we can develop tests and new treatments for long COVID”.